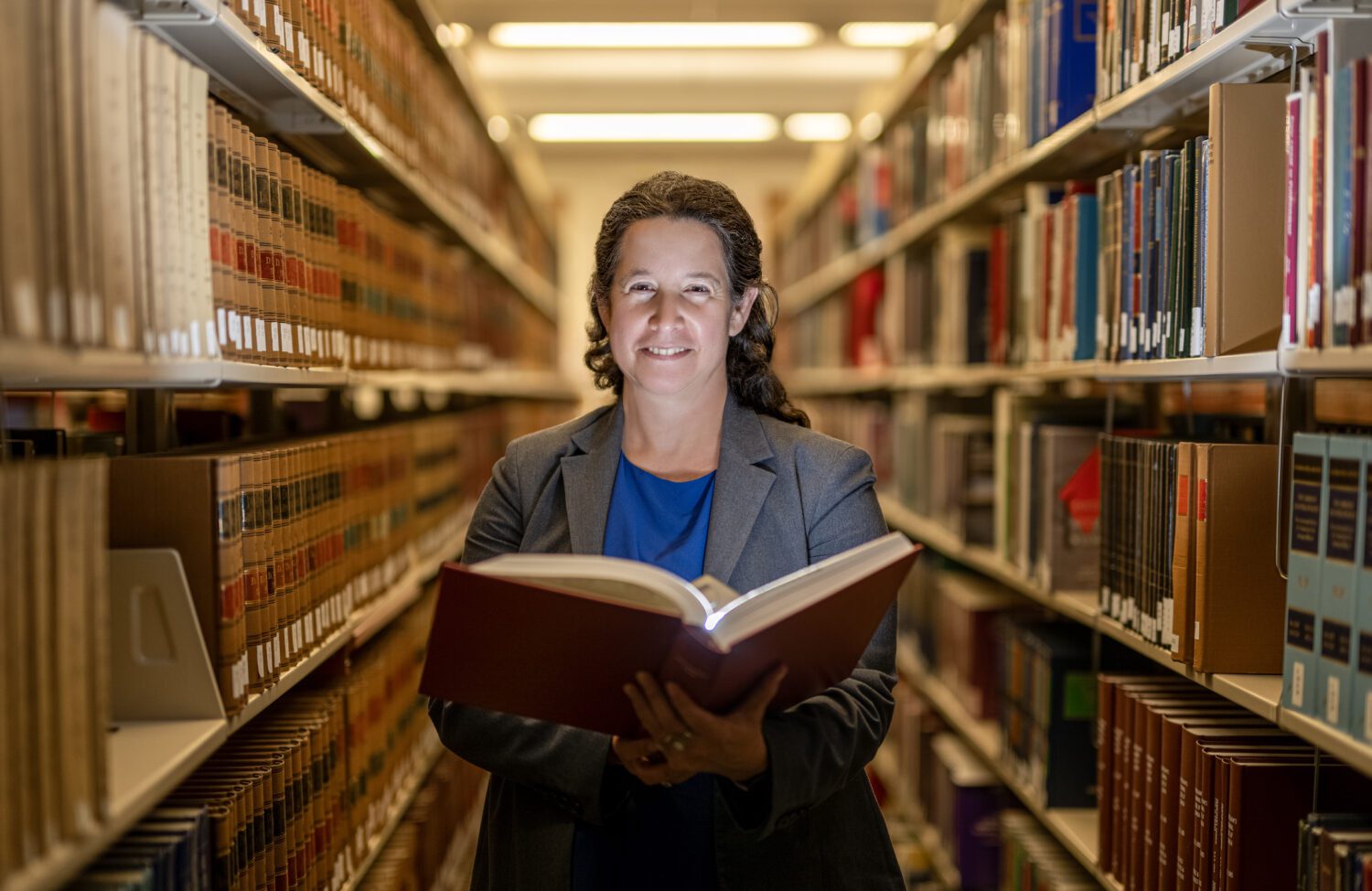

How Professor Dorit Reiss Became a Leading Voice in Vaccine Law

A leading researcher and voice in vaccine law and policy, Professor Dorit Reiss helps the media and the public make sense of a rapidly evolving federal health policy landscape.

- Professor Dorit Reiss is a leading national voice on vaccine law, regularly interviewed by major outlets like CNN, NPR, and The New York Times.

- Her scholarship examines how law, science, and public health collide—especially as federal vaccine policy undergoes sweeping change.

- At UC Law SF, Reiss connects legal theory to practice, preparing students to tackle complex challenges in law practice and policymaking.

Viruses don’t respect borders, and they don’t care about your politics.

That’s the message Professor Dorit Reiss wants the public to understand as the federal government enacts sweeping changes to vaccine policy under U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

“If you have cells, they’ll take you,” Reiss said. “That’s all viruses want.”

For over a decade, Reiss has studied how vaccine law intersects with science, public health, and individual rights. Her work covers everything from how vaccines are approved and regulated, to how governments can legally encourage—or in some cases, require—vaccination, and how courts weigh religious and personal freedoms against the collective good.

Her deep expertise has made her a go-to voice in the national media amid what she calls the most dramatic policy shift on vaccines in decades.

“They come to me because I know the legal framework,” she said, “and I’ve gotten used to explaining it to people who aren’t legal scholars.”

A Critical Voice Amid Rapid Change

In recent months, Reiss has spoken to The Washington Post, CNN, NPR, and other major news outlets, raising concerns about procedural breaks and ethical questions surrounding Kennedy’s decisions. Among them: halting Covid-19 booster recommendations for certain groups without standard expert review, installing vaccine skeptics on influential advisory boards, and dismissing career staff from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When a newly appointed advisory panel rescinded flu vaccine recommendations in June, Reiss told The New York Times how off-the-record deliberations could undermine the vote’s legitimacy and potentially violate the law.

She’s also concerned about long-term fallout. Layoffs in public health agencies and cuts to research funding, she said, may take a decade or more to undo.

“Manufacturers are looking at this and asking, ‘Should I invest in this new vaccine?’” she said. “We will lose investment, and it takes time to research, create, and distribute vaccines.”

From New Mom to Vaccine Law Scholar

Reiss’ focus on vaccine law started in 2010, shortly after her first child was born. A science blog comment denying the safety of whooping cough vaccines caught her attention—and sparked a scholarly interest that’s never faded.

She soon discovered a rich and underexplored legal landscape. Her writing has addressed everything from personal-belief exemptions and outbreak-related litigation to how vaccine skeptics challenge public health laws through lobbying and lawsuits.

She has published widely in top-tier journals—including the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, and University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law—to name a few.

“Professor Reiss is not only a nationally recognized vaccine law expert—she is also a prolific scholar whose work influences real-world policy debates and inspires students and colleagues,” said UC Law SF Provost & Academic Dean Morris Ratner. “She embodies the strength of our faculty in bridging rigorous scholarship and public engagement.”

Exploring the Real-World Impact of Law

Growing up in Israel, Reiss was drawn to the social sciences. A family member encouraged her to pursue law, calling it “the most practical” path in the field. She earned a degree in political science and law from Hebrew University of Jerusalem, then moved to the U.S. to pursue a Ph.D. in jurisprudence and social policy at UC Berkeley.

What captivated her was seeing how the law shapes on-the-ground outcomes.

“I found it fascinating,” she said. “The connection between legal arguments in court to real-world policy changes that affect people’s lives.”

In graduate school, her curiosity led her to explore how bureaucracies regulate industries like telecommunications and energy.

Eventually, she turned her focus to vaccine law—a field where science, public health, and policy collide. She saw a chance to apply her knowledge of legal systems and bureaucratic structures to one of the most high-stakes areas of public policy.

“It’s an ever-moving subject,” she said, “and it’s never boring.”

Today, that deep curiosity is reflected not only in her scholarship but also in the classroom, where she brings the most urgent legal questions into her discussions with students. She teaches courses covering tort law, administrative law, vaccine regulation, courts and politics, and statutory interpretation in the health law space.

Provost & Academic Dean Morris Ratner recognizes Professor Dorit Reiss as a leading and influential vaccine law expert whose scholarship not only informs national policy debates but also inspires students and colleagues.

Shifting Legal Ground

In her early research, Reiss was struck by how firmly U.S. courts have supported the government’s authority to protect public health.

“We have a robust jurisprudence that says yes, a community can act to protect its public health,” she said, citing Jacobson v. Massachusetts, a 1905 Supreme Court decision that upheld smallpox vaccination mandates.

But the high court’s more recent rulings during the Covid-19 pandemic signal a shift, prioritizing religious liberty over public health restrictions in multiple cases—and potentially giving vaccine opponents new legal ground.

“If courts keep chipping away at these foundations, it could seriously undermine our ability to respond to future public health crises,” Reiss said.

She also notes how the pandemic has deepened political divides around vaccines.

“We’ve seen a strong connection form between political identity and vaccine rates,” she said. “We’re seeing an increase in vaccine hesitancy related to political identification.”

A Landscape of Misinformation

Through her research, Reiss said she was surprised by the extent of misinformation spread by vaccine opponents.

“I thought some people may be misguided or misinformed but still sincere,” she said. “I didn’t expect to see such blatant falsehoods.”

She cited persistent claims that the FDA never licensed Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine—even after formal approval—and Kennedy’s assertion that vaccine makers have “zero liability,” despite his involvement in litigation showing otherwise.

“Congress created a compensation system for vaccine injuries that limits liability,” she said. “But manufacturers are not completely immune, and since he was involved in suing them, he knew that.”

Reiss regularly helps debunk myths, such as the idea that vaccine-preventable diseases are mild or treatable with unproven remedies. She also hears recurring concerns about ingredients like aluminum salts and formaldehyde, noting how the amounts used in vaccines are too tiny to be unsafe.

She’s alarmed that false and unproven claims are now echoed by federal officials.

“They are spreading misinformation with the seal of government,” she said.

Public Duty and Personal Stakes

Reiss’s commitment to this work is deeply personal. She has friends whose children are immunocompromised or were permanently harmed by preventable diseases.

“Nobody—certainly nobody’s children—should die or be harmed by a preventable disease,” she said.

That belief keeps her going, even in the face of threats and harassment from critics.

“If someone is pushing against me, I’m going to push back,” she said.

Professor Dorit Reiss has raised alarms about the potential fallout from policy changes, budget cuts, and mass layoffs of experienced staff at federal public health agencies like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Outbreaks Know No Borders

Since Kennedy took office, Reiss has tracked big changes in federal public health policy—from mass layoffs of experienced staff to removing experts from key advisory panels. She fears the fallout will be nationwide.

“California has robust vaccine laws,” she said, “but there’s no smoking section on this plane. If there’s more measles in other states, it will hit us too.”

This year, at least three people—including two children—died from measles in the U.S., and two infants died of whooping cough in Kentucky. Last year saw at least 10 whooping cough deaths, according to the CDC.

For Reiss, the link is clear: declining vaccination rates, driven by misinformation, are fueling preventable tragedies.

“It bothers me that people are misled into not protecting their children,” she said.

The Frontlines of Public Health

Although legal protections make it difficult to hold government officials accountable for spreading misinformation, Reiss believes individuals and institutions still have tools to fight back.

State governments can step in to cover funding gaps, mandate insurance coverage for vaccines, and form their own advisory panels, she said. Medical associations can publish science-based guidance. Private organizations can provide data on disease outbreaks, and community organizations can amplify trusted voices.

“States and private actors can also litigate,” she said, “or file amicus briefs. And they can speak up—loudly.”

Ultimately, she believes the debate over vaccine safety must also be won in the court of public opinion.

“We need to do the groundwork of reaching hearts and minds,” she said. “And we need trusted voices to reach individuals in areas with low vaccination rates.”

At UC Law SF, Reiss continues to lead that effort—not just through public commentary and scholarship, but by training future lawyers to understand the real-world consequences of legal decisions that shape public health.

“We need lawyers and policymakers who understand how the law can save lives,” she said. “That’s what I hope to instill in my students.”