Research by UC Law SF's David Faigman and Colleagues Spurs Bar Exam Reform in Nevada and Beyond

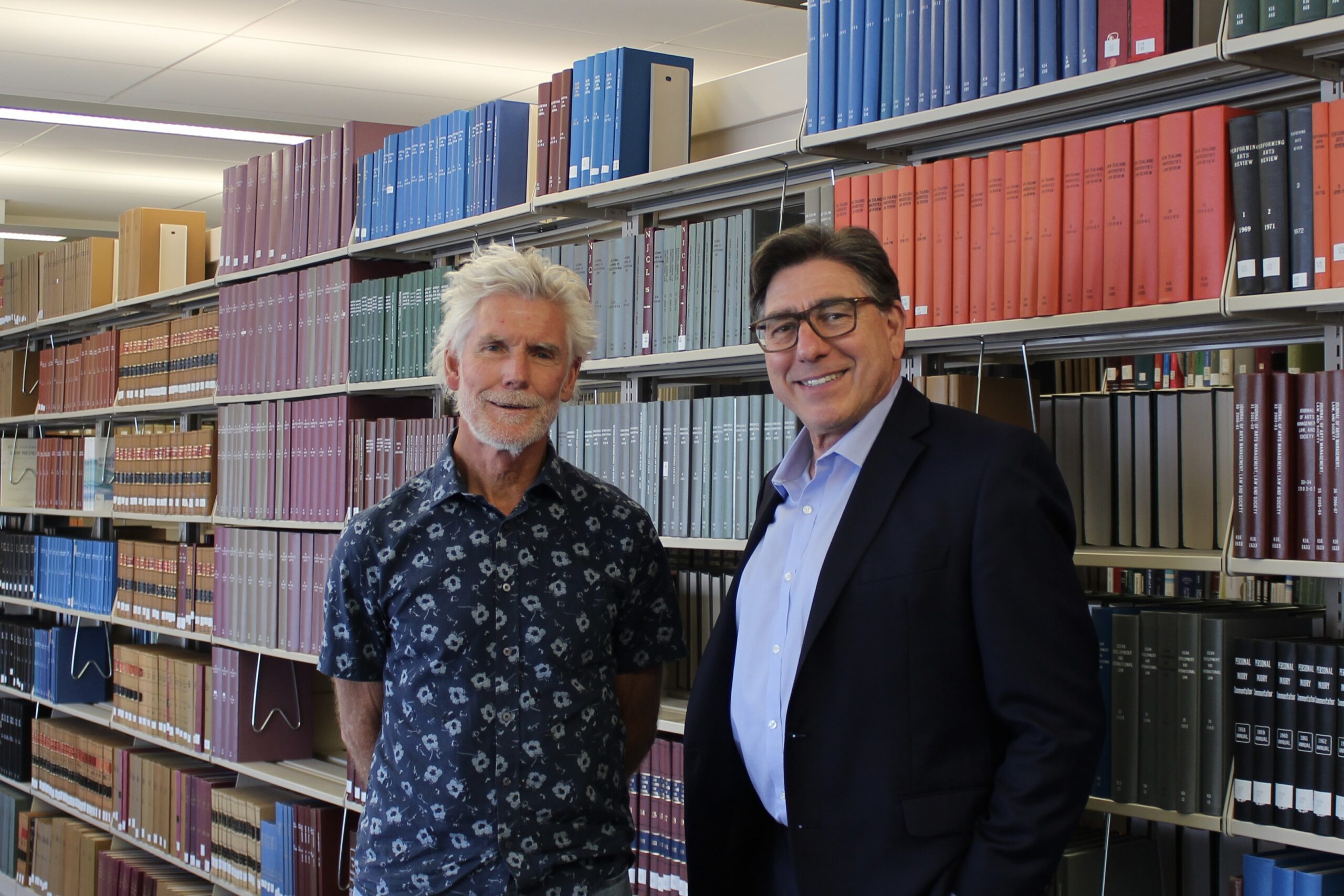

Spirited debates between Rick Trachok of the Nevada Board of Bar Examiners and David Faigman of UC Law San Francisco led to a landmark study showing little correlation between bar exam performance and attorney competence.

- UC Law SF leaders co-authored a first-of-its-kind study showing bar exam scores don’t reliably predict attorney competence.

- The Nevada Supreme Court used the study’s findings to overhaul its licensing system, creating a new pathway for lawyers.

- The research is fueling a national movement as other states reconsider the future of the bar exam

As states across the country reexamine how attorneys get licensed, two leaders from UC Law San Francisco co-produced a landmark study that helped change the way the state of Nevada admits attorneys to practice law.

Chancellor & Dean David Faigman and Assistant Chancellor & Dean Jenny Kwon co-authored a first-of-its-kind study examining whether performance on the bar exam accurately predicts how well a lawyer will perform at their job. Their findings—published in the Journal of Law & Empirical Analysis last summer—directly contributed to Nevada’s decision to overhaul its licensing system.

Working with a team of statisticians and legal education experts, the authors analyzed the on-the-job performance of 524 recently licensed Nevada attorneys. Using survey data from attorneys’ peers, supervisors, judges, and self-assessments, they compared the evaluations against each attorney’s bar exam scores.

The authors concluded that while the bar exam poses a major obstacle to entering the legal field, it falls short as “a robust indicator of what it takes to be a ‘good’ lawyer.”

Assistant Chancellor & Dean Jenny Kwon, whose research expertise and doctoral studies focused on educational effectiveness, shaped the landmark study on Nevada’s bar exam and its role in predicting attorney competence.

A Debate That Sparked Change

The roots of the study date back to 2016, when a record-low bar passage rate in California prompted Faigman to pen a May 2017 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times criticizing the state’s unusually high cut score for passing the bar exam. He argued that California’s threshold of 144 was needlessly exclusionary—blocking otherwise qualified graduates from becoming licensed while imposing financial, emotional, and professional harm.

Faigman had long been a critic of the bar exam format, arguing that lawyering competence can’t be measured by one’s ability to answer multiple-choice questions.

“The exam doesn’t look anything like what the practice of law looks like,” Faigman said.

His op-ed drew a strong response from Rick Trachok, a longtime member and chair of the Nevada Board of Bar Examiners and a lecturer at UC Berkeley. Trachok disagreed, defending the bar exam as a valid tool for assessing attorney competency. But rather than ending the conversation there, Trachok accepted Faigman’s invitation to come to UC Law SF’s campus for a face-to-face discussion.

What followed were a series of spirited debates about the efficacy of the exam. Faigman asked a question that stuck with Trachok: “Do you think California lawyers are better than New York lawyers just because our cut score is higher?” That question—and the lack of empirical data behind either position—sparked an idea. What if someone actually studied whether bar exam scores correlate with lawyer effectiveness?

As it happened, Trachok had access to the kind of data such a study would require through his work with the Nevada Board of Bar Examiners. Together, he and Faigman developed a research plan, ultimately receiving approval from the Nevada Supreme Court and grant funding from AccessLex, a nonprofit that supports legal education research.

Building a Groundbreaking Study

Rather than remain entrenched in opposing views, Trachok and Faigman turned debate into collaboration—producing data that shows bar exam scores bear little connection to real-world lawyering skills.

Kwon got involved in the project soon after joining UC Law SF as Assistant Chancellor & Dean in 2019. With a doctorate in education and strong background in project management and education research, she contributed her expertise as a researcher and co-author.

“In my field, the notion that standardized tests don’t always test what you think they test is generations old,” Kwon said. “They often measure test-taking ability—or access to expensive prep resources—rather than genuine competence or potential.”

The study used performance metrics developed by UC Berkeley Professors Marjorie Shultz and Sheldon Zedeck to evaluate a range of legal skills, including analytic problem-solving, understanding legal concepts, spotting relevant facts, writing quality, and more.

The results were striking: Bar exam scores bore little relationship to actual job performance. In fact, nearly half of those who failed the exam on their first try performed just as well—or better—in practice than those who passed, according to surveys.

Faigman and Kwon collaborated with multiple co-authors on the study, including Trachok; Jason M. Scott and Fletcher Hiigel of AccessLex; Stephen N. Goggin of San Diego State University; Sara Gordon of the University of British Columbia’s Allard School of Law; Dean Gould of the State Bar of Nevada; and Leah Chan Grinvald of the University of Nevada’s William S. Boyd School of Law.

The study authors also highlighted racial disparities in bar pass rates. In 2021, white law school grads outperformed their Black peers by 24 percentage points, their Hispanic peers by 13 points, and their Native American peers by 15 points, according to American Bar Association (ABA) data.

The co-authors noted that these gaps have consequences for the legal profession. According to data cited in their study, 19% of practicing attorneys identified as people of color in 2022, despite comprising 40% of the U.S. population.

“We are keeping a more richly diverse lawyer pool from entering the profession,” Kwon said.

The Nevada Supreme Court cleared the way for a landmark study and approved sweeping reforms to the state’s attorney licensing system. (Photo by Raul Jusinto)

Nevada Adopts a New Path

In May, the Nevada Supreme Court adopted a new three-part licensing system—dubbed the Nevada Plan—that will take effect in February 2027. The plan was developed by a task force on which Faigman served. It replaces the national Multistate Bar Exam (MBE) with a more tailored and practical approach.

The new bar exam process includes:

- A multiple-choice foundational law test, offered up to four times a year and available to take after the third semester of law school.

- A supervised practice requirement of 60 hours, which can be fulfilled through clinics, externships, or pro bono work.

- A Nevada-specific performance test given shortly after graduation.

Most components are designed to be completed during law school, allowing graduates to enter the profession more quickly. They also include more relevant and meaningful measures of competence, according to Trachok.

Trachok credited Faigman with advocating for a supervised practice element—comparable to medical residency—and suggesting that foundational law subjects, such as torts, civil procedure, and evidence, be tested earlier in law school.

“It never made sense to test subjects several years after you take them,” Faigman said. “You’re basically relearning all this material.”

Trachok also emphasized how Faigman’s openness to engage in constructive dialogue helped spark the groundbreaking research and major reforms that have reshaped Nevada’s attorney licensing system.

“I would not have been willing to jettison the MBE but for this study,” Trachok said. “This all started with our conversation in his office all those years ago.”

A National Movement

Chancellor & Dean David Faigman serves as a leading national voice on rethinking how attorneys enter the legal profession.

Nevada’s move comes amid a national reevaluation of bar exam practices. In May 2024, the ABA formally endorsed alternatives to the bar exam for the first time in its 103-year history of supporting standardized testing.

States like Oregon and Washington have already implemented licensing pathways that bypass the bar exam. States like Minnesota and Utah are currently considering similar proposals.

“Some states are now looking at what we’re doing in Nevada,” Trachok said. “They’re very interested.”

Last year, California adopted an $8.25 million plan to develop its own bar exam. After widely reported issues with a new online version in February, Faigman joined 13 other deans from ABA-accredited law schools in urging the California Supreme Court to improve the exam and provide remedies to affected students.

Beyond addressing immediate issues with the California bar exam, Faigman supports broader changes to how lawyers enter the profession. He’s particularly interested in interstate reciprocity, where states would recognize bar passage from other jurisdictions, supplemented by state-specific assessments.

“The future would be best served by a single national exam, supplemented as needed for state law,” he said.

Looking back, Faigman said a study on bar exam efficacy should have been done decades ago—but he’s proud that it finally occurred and has helped move the conversation forward.

“There have been serious problems with the bar exam for more than 40 years,” he said. “Now the momentum is finally shifting, and I’m proud that our work played a part in the movement for change.”