UC Law SF Works with Health, Education Experts to End School-to-Prison Pipeline

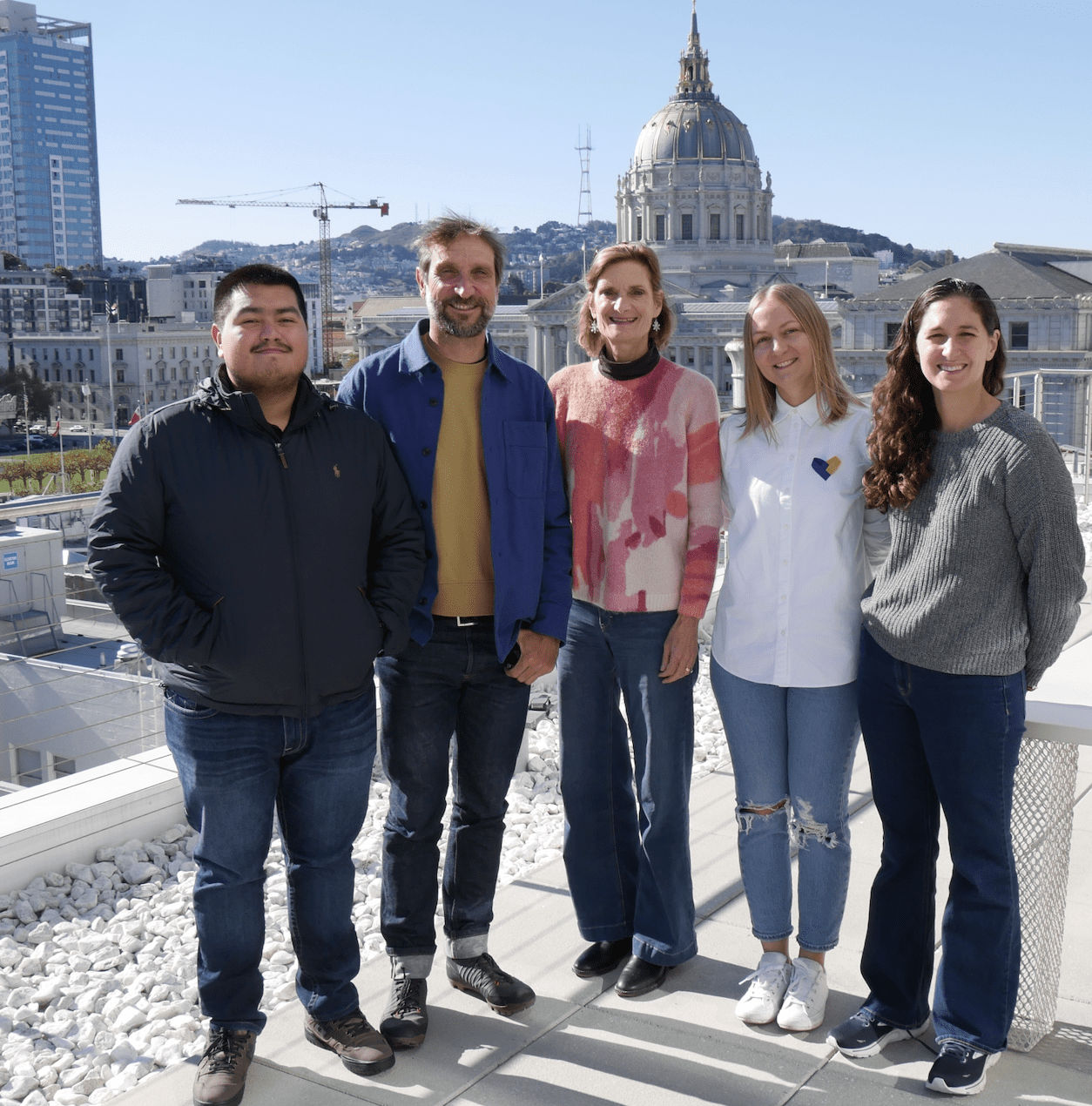

Administrative Assistant Jorge Castaneda, Senior Principal Investigator Andrea Lollini, Executive Director Liz Steyer, and Senior Researchers Maryna Tsapok and Sara Hundt (left to right) are part of a team working for the Bench to School Initiative and California Institute on Law, Neuroscience and Education at UC Law SF.

At any given moment, thousands of young people—disproportionately youth of color—occupy juvenile detention centers in California, raising the odds that they’ll spend time in prison as adults and face more challenges finding jobs, housing, and thriving in society.

At UC Law San Francisco, researchers are working as part of a team across three California campuses to learn what factors lead young people to get caught up in the juvenile justice system and how to better educate and serve those already in the system.

It’s part of the Bench to School Initiative through the California Institute on Law, Neuroscience and Education (CA Institute), a collaboration between UC Law SF, UCSF Dyslexia Center, and the UCLA School of Education. It brings together researchers, practitioners, and policy experts to design projects with the goal of ending the school-to-prison cycle for generations of children.

“The California Institute aims to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline in California by addressing literacy outcomes in school settings through a collaborative multi-stakeholder and multidisciplinary approach,” said UC Law SF Chancellor & Dean David Faigman, who has championed the collaborative work.

Established by the California Legislature in 2021, the initiative coincides with ongoing reforms to the state’s juvenile justice system. As part of those efforts, the state shut down the last of its state-operated juvenile detention centers this past June, transferring detainees to county facilities.

Liz Butler Steyer is Director of the CA Institute and Executive Director of the Bench to School Initiative at UC Law SF. She explained that the project will advance interdisciplinary research on the population of young people who touch the juvenile justice system. This will enable researchers and policymakers to better understand justice-involved youth and their needs, many of which center around learning disabilities.

“These insights will help us reform the legal, educational, and health/mental health systems to better serve them so fewer young people are incarcerated and those who are in the system are better served,” she said.

One of the initiative’s many projects is a deep dive into data collected on 2,500 young people in juvenile detention centers statewide. “We want to understand the demographics in detail, including correlations with disabilities, school performance, and the socioeconomic environment those kids come from,” said Senior Principal Investigator Andrea Lollini.

The research findings will help shape proposed reforms to the state’s health, education, and legal systems. Though such reforms come with costs, Lollini said he thinks they will save taxpayers money in the long run by helping to reduce the state’s prison population. California spends over $100,000 per incarcerated person each year, adding up to more than $14 billion annually.

“If you don’t step back and look at why folks are in the school-to-prison pipeline and don’t do thoughtful interdisciplinary research, you can’t come up with conclusive solutions,” said Senior Researcher Sara Hundt.

Researchers are also studying what all 50 states offer in terms of early childhood screenings for learning difficulties, such as dyslexia. The screenings can lead to interventions, such as specialized learning plans, to address issues that may cause children to act out. Prior research shows that resulting disciplinary actions, such as school suspensions, increase the likelihood that kids will get caught up in the criminal justice system as adults.

“We want to understand how other states are dealing with this problem,” said Senior Researcher Maryna Tsapok. “How do they detect the problem? How do they intervene? How is it organized? Who’s responsible? How much money does it cost?”

The team also plans to do in-depth institutional surveys of those who work on the front lines educating kids in detention centers. The surveys will help researchers better understand issues affecting educators and students alike—knowledge that will support the development of more effective literacy-based interventions to improve educational outcomes.

Additionally, the CA Institute is working to provide assessments and support to the students at Rancho Cielo Youth Campus. Rancho Cielo is a former juvenile incarceration center turned vocational training, diploma education, counseling, and life skills residential center for underserved youth in Monterey County. Building on the strengths of the innovative education program there, the Institute will assess how to support better outcomes for vulnerable populations across California.

Steyer said she looks forward to presenting findings from the various research projects to policymakers so they can start implementing reforms that will make a lasting impact on the lives of young people across the state.

“By taking advantage of the wealth of expertise among our team, we can drive systemic change in law, education, and neuroscience on behalf of California’s youth,” Steyer said.